Outer Wilds: The Transformative Power of Uncertainty and Faith

Part 3: The Fear that Kills the Hearth

The entire death of the universe is a real bummer, but it doesn’t hold a torch up to the true moments of horror in the game: the Echoes of the Eye DLC.

The DLC was released after the game. While most video game DLCs can be seen as bonus content for an already finished game, The Echoes of the Eye DLC is necessary to get the complete Outer Wilds experience. Without it, the game is still a powerful experience, but with it, the final experience is greater than the sum of its parts.

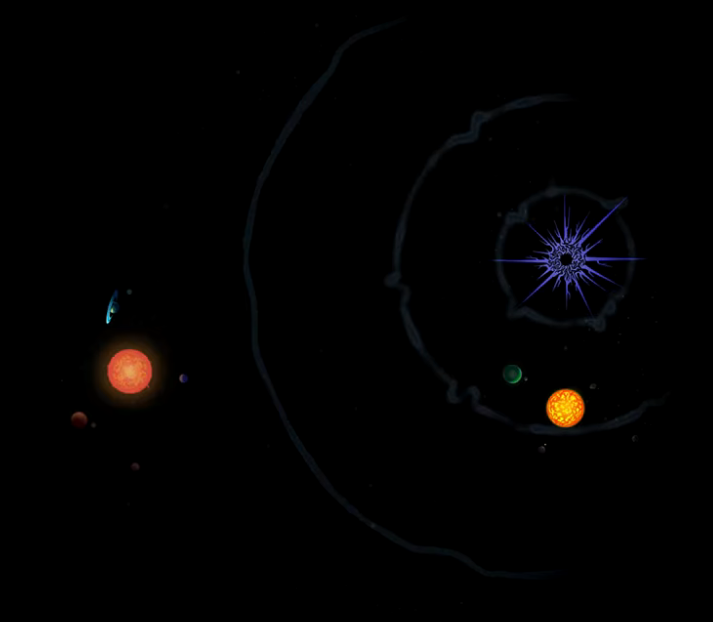

In Echoes, as I’ll call it, you stumble upon a massive cloaked space station called the Stranger in a perpendicular orbit around the sun. Finding the station is like a scene out of a horror movie. You first see the shadow of the stranger, a black disk passing over the surface of the sun. As you fly toward the anomaly, everything goes dark and you pass through the ship’s protective field, and you find yourself drifting towards an ominously stark hangar as the game’s music becomes chilling.

In contrast to the earthy and elegant structures of the Nomai, the architecture here is dark, brutal, hostile.

Another surprise comes when you use your lantern to activate the light-sensitive mechanism that opens the airlock and allows you inside. Inside is a ring world, a long ring of water flowing through this place in an endless loop.

It’s made to look like a natural landscape with trees and hills dotting the landscape as well as humble cabin-like wooden structures similar to the Hearthian ones. In fact, at the surface there seem to be a lot of similarities between this ring world and Timber Hearth, but the closer you look, the more the façade disappears and you realize there’s something very wrong about this place.

For starters, its empty.

Timber Hearth has the warmth of community, cozy fires, music, children playing, and the bustle of a small town.

The Stranger is a dead world. The water in the river is the only thing that moves there. Even the moss covered trees seem ominous compared to the lush pines back home. All the structures are abandoned, and all you find are traces of life from long ago: a burned-out building, slide reels, faded portraits. The former inhabitants look back at you like ghosts from the past.

The former inhabitants are never named in the game, but the community has taken to calling them Owlks.

As you explore their abandoned ring world, the game takes a drastic shift in tone. What once was a wholesome game about exploration and curiosity, slowly transforms into a horror mystery. While the game offers players the option to play in a mode that “reduces frights,” the fear in this part of the game is essential, as essential as the secrets you uncover.

The only way to proceed and uncover the truths of the Stranger, is to confront those fears and overcome them. The mechanics in Echoes reward players for taking risks and delving into the darkness, but there’s also a price to pay for being reckless, and its a fate far worse than your character dying.

The death loop mechanic causes most players to eventually stop fearing or avoiding death. When I started the game, I’d go to great lengths to avoid damaging my ship or getting swept up by a tornado in Giant’s Deep. Most games punish players most severely if their characters die, so its a natural instinct to avoid this fate if possible. But the loop-mechanic of Outer Wilds soon renders death powerless.

When you die in the game, you don’t lose any saved information or logs, there are no items or gold that disappear, and you always start back at that same bonfire on Timber Hearth. Death in Outer Wilds becomes more of an annoyance after a while. It can be frustrating if it happens when you’re close to reaching a particularly difficult section, or before you can read all the information in a new area. It’s frustrating because it means you lose time, time you’ll have to spend backtracking to the same area. But there is nothing that dying places out of reach permanently. It doesn’t limit the kind of ending you can obtain, or make any lasting changes to the world or your character.

A lot of credit is due to the developers at Mobius. Their challenge was to create a DLC that could provoke genuine fear in a game where dying is rendered inconsequential.

Without explaining the many reasons why (as that would be its own deep-dive), they succeeded.

Confronting the psychological and atmospheric horror elements laid out for the player allows you to learn the fate of the Owlks.

They were a civilization far older than the Hearthians and even the Nomai. Like the Nomai, they were drawn to the distant signal of the Eye of the Universe, but without the ability to warp there like the Nomai, they had to prepare for a long and final journey. This voyage would cost them their home-world, as the materials to build this self-sustaining ring world used up all of their home’s natural resources.

Having stripped their world of all life, they set off towards the Eye on what is implied to be an incredibly long voyage aboard the Stranger, that same ring-world you discover at the start of Echoes.

They arrive at the Eye by following its signal but are confronted with a disturbing vision. Using one of their many light-based technologies, they are able to “look” into the eye and receive a vision from it. The Eye shows them the inevitable fate of the universe as they see the eventual death of all planets and stars. in the vision, the Owlk sees himself disintegrating into a skeleton, then a pile of bones.

Before the vision fades, we see new life, green grass and plants growing from the Owlk’s skull. The vision ends, and the Owlk’s former reverence towards the Eye turns to fear, then to hatred.

The Owlks retaliate by burning their temple dedicated to the Eye of the Universe and build a probe designed to create a permanent forcefield around the Eye of the Universe, effectively isolating its influence and containing its signal. In their fear and anger, their former curiosity and reverence towards the powerful Eye leads them to block it off from the universe. Not only are they sealing away something they cannot comprehend or control, but they are preventing any other civilization from being able to locate and interact with the Eye.

The Owlks appear to be a species obsessed with recording and preserving memory based on the many libraries of reels found around the Stranger. One such reel reveals that in time, their hatred turned to sorrow, regret, and nostalgia. As they arrived at their final destination, only to reject it, they painfully remembered the homeworld they destroyed to get there. Even if the Owlks could somehow return to it, there would be nothing left to return to. They sacrificed everything for the call of the powerful unknown, and they came to regret their choice as they had nothing left to show for their sacrifice.

It’s never explicitly stated how long the Owlks live, but there are clues to suggest their lifespans are incredibly long (hundreds if not thousands of years long) as they are few in number and the Owlks that left their world seem to remember their home. The average distance between stars in our own Milky Way is 5-light years. The Owlks did not have faster-than light travel so any trip to another star would take hundreds to thousands of years, since its never revealed how close to their own system the Hearthian system is.

This detail is important as it begins to explain the Owlk’s obsession with tradition, preservation of memory, and their fear of change. If you could live for thousands of years, the prospect of a sudden an unexpected death might seem that much more terrifying when it could rob you of centuries worth of memories, joys, and experiences.

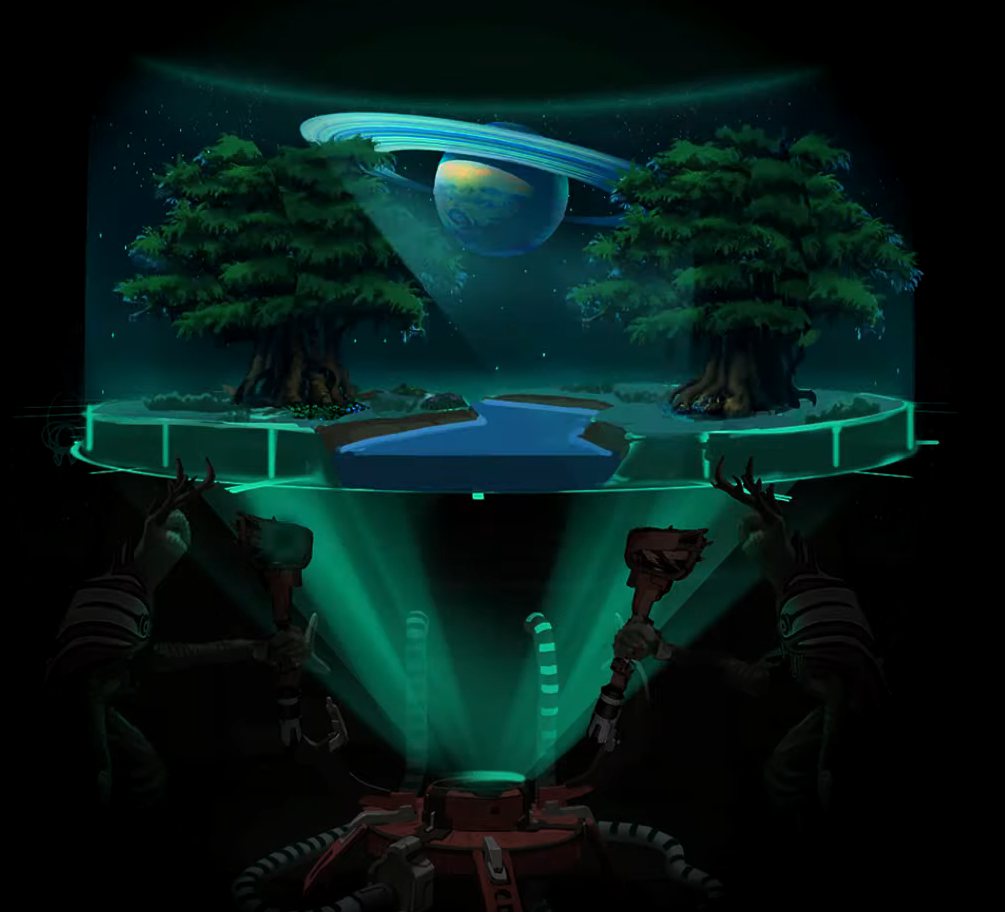

Eventually the Owlks devise an imperfect solution to their desire to recreate the home. Rather than live out the rest of their days in their ring-world colony, they design technology that enables them create a virtual simulation of their home world. By using a lantern-like artifact and sleeping around a green fire, the Owlks can then enter an eternal dream of home with the others, where they can live out the rest of their days in the comforts of the past.

And this is exactly what they do.

Their consciousness is now doomed to roam amongst the constraints of their virtual world. They congregate in dusky halls, singing a mournful song to remember the rings of the gas planet their homeworld orbits. This song, “Elegy for the Rings” is a recurring motif in Echoes. You will hear this melancholy harmony echoed throughout the Stranger, both in the game’s atmospheric soundtrack, and also diagetically from the Owlks who gather to sing this elegy and remember the loss of their home.

When you find one of these dream-chambers for the first time, you’re greeted by a grisly sight. A ring of desiccated corpses surround the fire. Disturbingly, their lanterns are still lit, implying that they are still somehow connected into their virtual dream-world.

Although disturbing, the true moments of fear that Echoes serves happen only after dozing off by the green fire holding a lantern. Doing so allows you to fall asleep only to awake and find yourself in their artificial dream world. Here, Echoes forces players to walk stretches of darkness with only a faint lantern to guide them.

You might have noticed some parallels between the Hearthians and their homeworld to the Owlks and theirs, and this is not a coincidence. I believe that the Owlks and their journey to self-isolation were designed to act as a cautionary foil to the plucky Hearthians. Their story is a tragedy of what happens when the desire to conserve their hearth combined with a refusal to come to terms with change and uncertainty, dooms them into a self-imposed spiritual death far worse than any other fate the universe had in store for them.

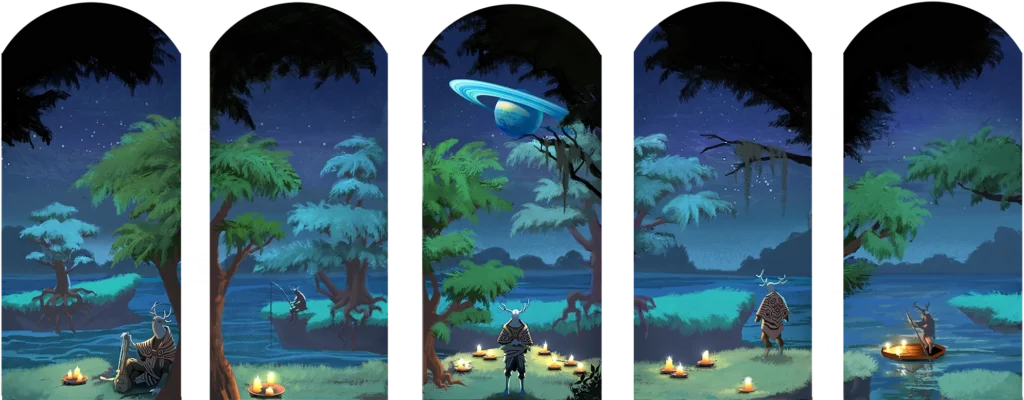

The Hearthians and the Owlks both share a homeworld with many similarities. Although possessing technology to enable space travel, both civilizations are deeply entrenched in their natural surroundings and continue to live in wooden structures that complement their natural surroundings rather than dominate them. The world of the Owlks is one of lush forests, flowing rivers, blooming flowers. Its beauty is undeniable: always cast in tranquil night, warm candles, torches and lanterns illuminating paths long the river, and communities of interconnected ornate wooden buildings that resemble the pole houses of Oceania.

Like the Hearthians, this is a species that values community, art, music, and gathering around a warm fire. These are all elements of the hearth: a home that is more than just a place to live, but a place of connected hearts and minds.

The difference between the two species emerges when the Owlks repurpose their entire homeworld into a ring colony for their journey to the Eye. You could argue this was a necessity, given the possible distance from the Eye and the length of the journey, but I believe the significant symbolic takeaway here is that the Owlks were so unwilling to leave behind their hearth, that they chose to bring it with them on their journey. This decision makes sense when viewed through the lens of their desire for preservation and their fear of change. Given their longevity, it might have made sense to send a small scout ship or build a ship without all the comforts of their home for their journey. Their insistence on recreating their homeworld as a ring-world was the first step of their undoing.

By destroying their hearth and remaking a simulation of it out of fear of leaving it behind, they have already destroyed what made it special and created only an approximation of its beauty. Even if they could have perfectly re-created their home world to take with them on their journey, their blue ringed planet that defined their night sky would would have still disappeared.

When travelling through space, the Hearthians only take with them a part of their home. A campfire, camping supplies, a musical instrument, some photographs. These are the sorts of things a hiker travelling through the wilderness might bring with them to remind them of home, but they’re all transitory in nature. There is courage in leaving the hearth, there is always an inherent risk of never being able to return. But the Hearthains understand that truly preserving the hearth means occasionally abandoning it, even if they might never return. There has to be an acceptance of loss in order to not destroy what you love.

One of the most important tenants of Buddhism is non-possession. Buddhists argue that it is possible to love without attachment, for love is selfless and attachment is selfish and comes from a desire to control.

“From a Buddhist perspective, attachment is a source of suffering and hinders spiritual growth. To overcome attachment, we must cultivate non-attachment, which can be achieved through meditation, mindfulness, and equanimity.”1

Hearthians have a considerably zen attitude when it comes to accepting things out of their control and going with the flow. This is especially true for Gabbro who comes to terms with the concept of dying in an endless loop fairly well and decides to spend his 22 minute loops relaxing in a hammock.

When faced with the cosmic vision from the Eye, they fixated on the certainty of death in the vision. Yet, they failed to see the importance of the renewal of life, thus missing the entire message from the Eye. The vision was communicating a cycle of death and rebirth, a form of endless renewal. But the Owlks could not see past their own mortality. Unwilling to confront their end, they did the equivalent of plugging their ears when they sealed off the Eye from the universe.

This was their second mortal error. The Owlks had done something remarkable by following the signal of the Eye and reaching it. They had the potential of tapping into unknown cosmic power and uncovering universal mysteries, but gave that up because they were unprepared to face the inevitability of death, not just their own, but that of the universe.

By creating a virtual dream of their home, they consigned themselves to a deeper isolation, even more removed from the home they mourned. While the ring world of the Stranger is not their home, at least the soil, the trees, the plants, and the water are all real, tangible artifacts from they home world. They can still feel and tend to the same trees that shaded their homes, still swim in the same waters. But they trade all of this for a more convincing illusion. Their virtual dream feels more like their home, and it might even be indistinguishable in certain ways. Their mind might experience the same smells and sights and touch of their homeworld, they can see the rings of the blue planet in the sky, but there is no escaping the lie. Abandoning their lantern causes them to step out of the rendered bubble of illusion and see the dream for what it really is, vectors and polygons in a computer.

Even if their homeworld could be replicated virtually down to the last grain of sand, they would still live with the knowledge that its all an illusion. This truth alone, would never let the Owlks restore their hearth to what it once was.

There’s a lodge in the dreamworld where many players encounter the first sign that there are others in this simulation. You see a projector playing a looping video on a screen. The video appears to be footage from their original world, like an old home-movie from a time long past. The projection is partially obscured by the moving shadow of an antlered head, an indication that one of the Owlks is sitting between the projector and screen, obsessively watching this looping footage of their home.

There is no better symbol of their self-imprisonment than this: a digitally preserved copy of an Owlk, watching a preserved footage of its homeworld inside of a virtual simulation of it, inside of a ring-ship designed as a simulation of the world they destroyed down to build. The layers of irony would be comical if they weren’t so tragic.

In trying to protect their hearth from uncertainty, they ended up sealing their hearth away from the world, each layer of artifice distancing them more and more from the source of their love and yearning.

The final nail in their coffin was to punish the single spark of hope and dissent that challenged their fear and might have steered them towards a better future. While in their eternal dream, one of the Owlks wakes up from the dream world and sneaks into the control panel, de-activating the probe that is sealing away the Eye and lets the Eye’s signal once again radiate through the universe.

It’s never clear what this rebel’s motivation but he is quickly and brutally punished. The Owlks re-activate the force-field around the Eye, destroy the controls so that nobody else can shut-off the containment bubble, and then seal the “prisoner” as he is known in an isolated dream pod. He is trapped not only in the real world, held in a bell-like structure submerged underwater, but also trapped in a virtual prison created especially for him in the dream world, unable to ever escape even in the dream.

Having dealt with the prisoner, they resume their eternal slumber.

By the time you find the Owlks they are dead, hollow husks. A part of them still lives, a preserved digitized consciousness imprisoned in an endless artificial dream.

You enter their dream by falling asleep at an eerie green artificial fire meant to mimic the cozy campfires that provide comfort and rest throughout the game. This fire and the lanterns lit by it, are symbols of corruption of the Owlk’s hearth. The fire is meant to bring them home, but instead it is their downfall. In this dream, the virtual Owlks hunt you down, still jealous of the illusion of home they desperately cling to.

But the ending of Echoes is bittersweet and cements an important part of the formula necessary to create the underlying spiritual message of the game.

If you can survive the harrowing pursuit of the Owlks in the dreamworld, uncover the remnants their own censored and shameful past, and successfully brave the darkness of the unknown, you are rewarded by meeting the prisoner. Up until this point you have every reason to believe that whatever the Owlks sealed away in this chamber is a source of great danger and evil, something so taboo that it had to be permanently sealed away and the keys destroyed. Entering the chamber requires faith that whatever is in there is worth confronting, that the truth of what is sealed away is worth the risk.

The player is then forced to accept that the only way to bypass the security systems and open the chamber is to die upon the green fire. This allows you to enter the dream-world in death instead of though sleep. As long as you sleep or die near the green flame, you can enter the dream world but once your physical body dies, there’s no going back.

As I said before, up until this point the average player would have died dozens of times and played though as many loops. It would seem that dying once more to access the final area of Echoes should be a piece of cake, but something about this death feels uncomfortably different.

There’s something very unsettling when entering the dream world through death: a uncertainty of what happens should your lantern go out in the dream world with no body to return to. The game is asking the player to make the ultimate sacrifice and embrace death in order to find the truth: this is something the Owlks were never able to do.

In a brilliant stroke of storytelling, the player is forced to succeed in overcoming the fear of death and uncertainty and make the difficult choices that the Owlks never could. In doing so, the Hearthian you control is assumed to have faith that it will lead to a better outcome.

This is where the player learns about the prisoner and he tells you his story. You tell him your story, too. Explain to him how his moment of rebellion allowed the Nomai to detect the Eye’s signal just long enough to warp to the right system, how you and the other Hearthans were able to build upon the successes of the Nomai to take up their mantle and continue their mission to find the Eye and unlock its secrets. The prisoner wails with joy, and leaves his sealed chamber.

You follow him to the bank of a calm bay of water. He leaves you his light staff, and a final vision of the two of you sailing away on a boat together toward a brilliant sunrise. This is the first and only time you see their homeworld in the light of day. You follow his footsteps in the sand and see they end at the water’s edge, no sign of him. You realize he extinguished his lantern and gave up the last remaining form of his life, escaping from his prison of illusion and ceases to exist.

Having no living body of your own to go back to, you can follow him into the water, extinguishing the light of the lantern and triggering a black screen and the credits for Echoes of the Eye.

This death does not feel like the end, it seems hopeful, even peaceful given the acceptance of it before it comes. The prisoner extinguishes his own lantern of his own volition, choosing to cease to exist, rather than live on forever in this prison of their own design.

On the other hand, the other Owlks are not so lucky.

Even they, in their attempts to preserve themselves among their memories for eternity falls apart in the end. Near the end of the 22 minute loop, as the sun starts to expand before its implosion, the Stranger’s sensors detect this danger and activate its solar sails to leave the solar system and escape the blast radius of the supernova. The Owlks were so weary of their own demise that they even thought ahead to the natural death of the sun they orbited and had a plan to escape this death whenever it reared its head.

When the solar sails deploy and the Stranger begins to careen away from the dying sun, cracks begin to appear in the dam that holds a reservoir of water and controls the flow of the circular river. The well-designed systems have also felt the strain of time, as have the Owlks whose bodies time has also turned to bones, just as the eye predicted in its vision to them.

Eventually the dam breaks, releasing a rush of water from the reservoir that floods the ring world and destroys nearly every building on it. One of the dream chambers is flooded instantly, the waters from the flood quenching the fire and destroying the inhabitants in the dream. If you’re in the dreamworld when this happens you can hear the agonizing screams of this group of Owlks as their conciousness comes to an end and they vanish.

The other dream chambers take longer to fall, but eventually they all collapse and succumb to the waters of the river. This river is an unbroken symbolic circle of life, endlessly flowing around the interior of the ringworld. In the end, their promise of forever comes crashing down on them, destroying their dream, and delivering the totality of death they tried so hard to escape.

Even the Owlks cannot escape Entropy. The Eye’s vision of their deaths came to pass, and so their many thousand-year dream must also come to an end.

In trying to escape the reality of death, the Owlks have also robbed themselves of the possibility of regeneration and rebirth. Their story ends with death because they could not overcome the trials of fear.

The cautionary tale of the Owlks and the glimmer of hope from your encounter with the prisoner serves as a powerful warning. The spiritual message of hope that many players cling to at the end of Outer Wilds would not be as impactful without seeing its dark counterpart.

I’m reminded of a quote by David Lynch, an director and artist known for his careful use of dark themes and imagery in order to accentuate the contrasting goodness in his films.

We all have at least two sides. The world we live in is a world of opposites. And the trick is to reconcile those opposing things. I’ve always liked both sides. In order to appreciate one you have to know the other. The more darkness you can gather up, the more light you can see too.

Echoes forces the player to also reconcile light and dark in trials of uncertainty in order to uncover and liberate the goodness that had been locked away by the fears of the Owlks.

The only real prison is fear, and the only real freedom is freedom from fear

Aung San Suu Kyi